A History of the Project - Part III

Dario Sattui

Castello di Amorosa: A History of the Project: Part III

After more than 15 years of research, I was ready to build my castle in the Napa Valley.

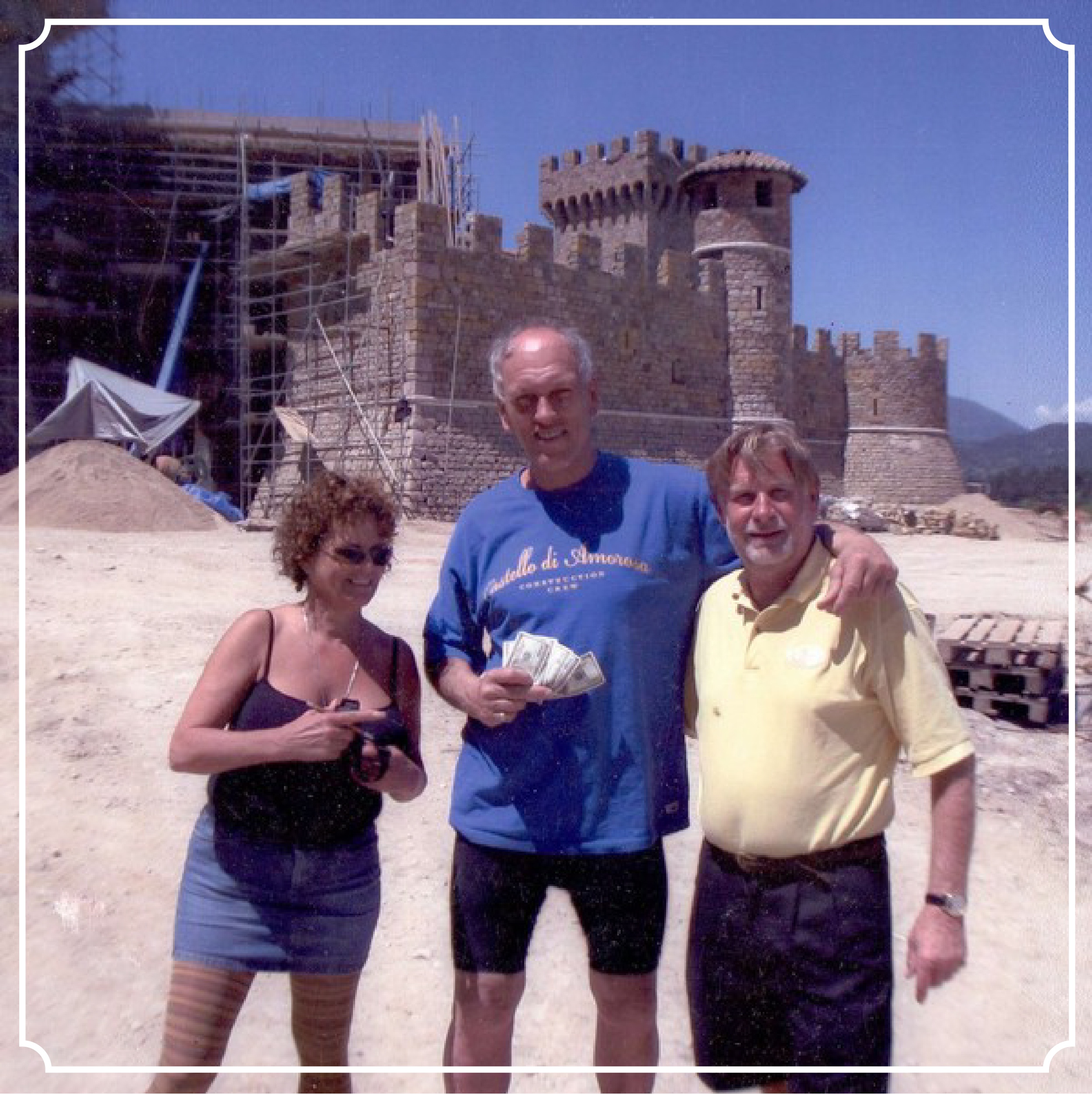

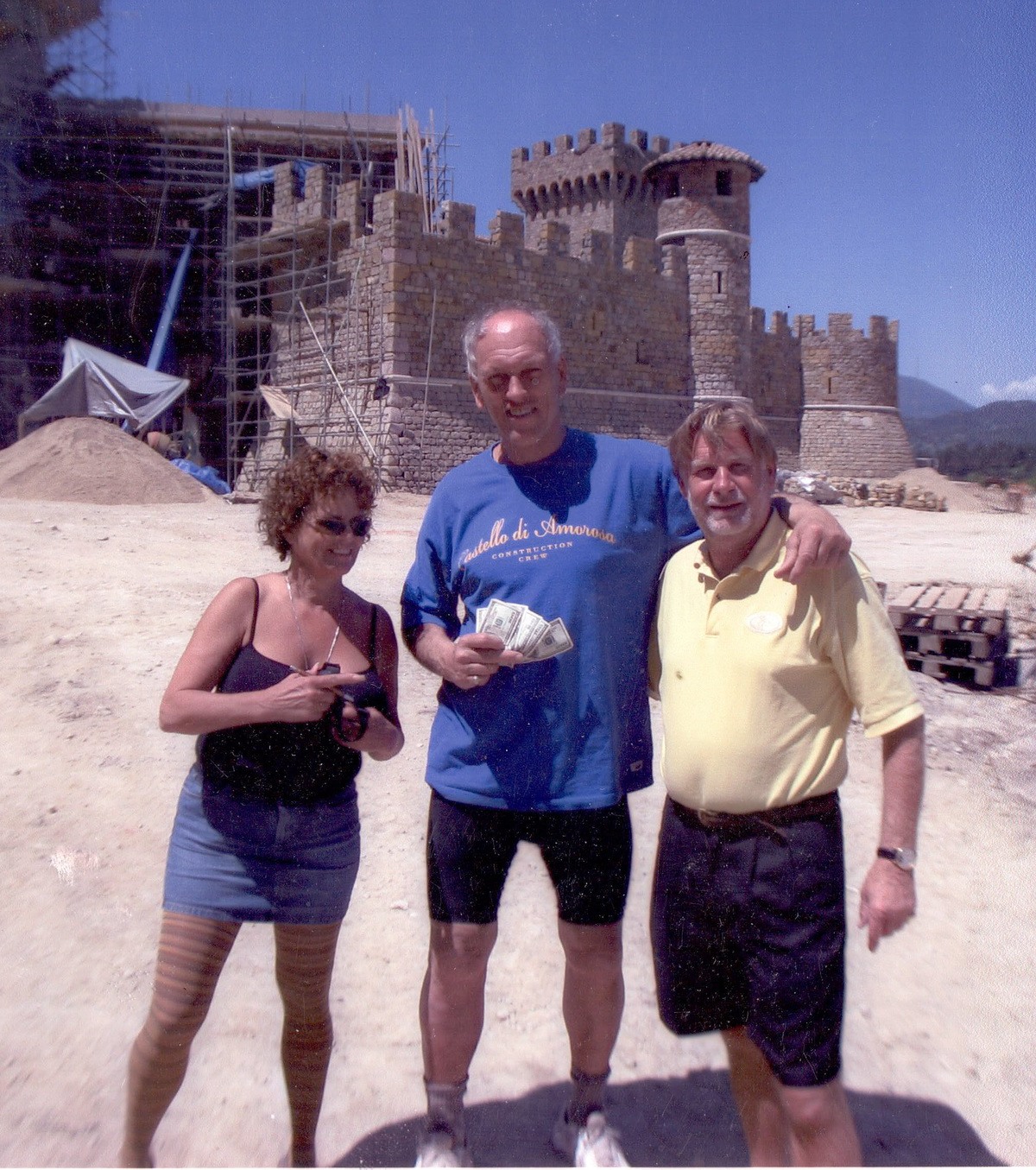

And I had my first paying customers, Peter Thomas. They love the Napa Valley. Photo taken April 29, 2006.

I had accumulated a wealth of knowledge on medieval architecture, a huge library of books, photos, plans and detailed sketches. I couldn’t wait to get started. The renovation of my historic Victorian at the bottom of the hill on the same property would have to wait. I was going to build my castle first.

Within a short time of acquiring property on which I would build, Lars Nimskov, the naval architect from Denmark, came from Italy and we began working on plans which were submitted and approved by Napa County a year later.

Lars Nimskov (in red jacket) oversees construction of Castello di Amorosa in 1998.

We would build the underground cave and cellars first. Then we would build the castle walls, towers, and all above ground structures. I had been saving my money for years. I was sure that with my savings coupled with current earnings I could manage financially if I were prudent in other areas. Construction I figured would take about five or six years. Boy, I was wrong on both accounts!

Dario Sattui, September 18, 2006. The Drawbridge is under construction. (Photo: Pat Daniels)

On January 5th, 1995, we began construction of 900 linear feet of caves. We hired a firm that used a Welsh mining bore which excavated horizontally into the hillside at a rate of 15 feet per day. In five and a half months, the caves were finished; the perfect environment for aging wine with cool, constant temperatures and high humidity. The problem was we now had a mountain of excavated, poor-quality soil we didn’t know what to do with.

And the excavating was just starting. We had three more underground levels (originally one level until I expanded the building) of cellars to excavate and then build. The mountain of dirt became progressively higher.

Fritz Gruber, the master builder from Austria and one of the few persons in the world who knew medieval building techniques, agreed to come for three months with six men. They were to build the first two rooms and show us how it was done. Shortly thereafter, seven men arrived and moved into my house along with Lars. None of them, save Fritz, spoke any English. My home had been turned into a boarding house. But I knew I had to skimp monetarily to see this project to completion.

Master builder, Fritz Gruber pictured with one of his works of art in Europe.

Three months later, Fritz and his men left for Austria. I was really concerned we would not be able to do complex medieval ceiling vaulting ourselves and we would have to stop building or construct ceiling which were not authentic. But Lars was very capable and, by observing for three months, figured out how to do it.

Through rain, occasional snow, cold, heat, and heavy winds, we built Castello di Amorosa, working six days a week, usually ten or more hours a day. Over the years, we employed builders from eight different countries and materials from five.

I kept changing and enlarging the plan, carried away with this obsession to build ever better and ever more. When things weren’t done absolutely authentically and correctly, we tore them down and started again. Along the way we kept referring back to source materials and photos, making sure that every minute detail was done properly.

As the years of building continued on, I divorced, lost my hair, became more wrinkled, was struck by a car crossing a San Francisco street, and endured a major flood and a slowdown of my energy. But I always kept building. The 5-6 year project expanded from the original 8,500 to 121,000 square feet and 107 rooms, all different. I went through my money- all of it. Then I sold all my stock to raise cash, often when the market indicated to do the contrary. When that money didn’t suffice, I sold my castle in Tuscany. I fired my housekeeper, then the gardener in an effort to save money to use in construction. I skimped everywhere I could to keep building. And the years of construction kept slowly rolling by. Instead of semi-retiring to Italy in 1994 as I had envisioned doing, I was working harder than ever at both V. Sattui, my original winery, and on building Castello di Amorosa. But I loved it. I couldn’t wait to get out of bed in the morning and hurry to the construction site.

Finally in 2005, I realized that I might not finish the project in my lifetime. I replaced Lars Nimskov, with whom I did not get along, but endured his bad temper because he understood what I wanted and was capable of doing it. I thought of hiring an American contractor, but those whom I had met lacked the knowledge of medieval construction and were intimidated by the project with no idea how to build it.

But through a friend, I found an Italian builder, Paolo Ardito from Bologna. We met at a freeway off ramp in Italy. We were wary of each other at first, but we both took a chance. He spoke virtually no English which complicated things, and out of necessity I communicated in my bad Italian. But somehow it worked. He brought over seven master masons whom I quickly sent back to Italy upon discovering that master builders they were not. I quadrupled the construction crew to 64 and we kept building.

Dario Sattui and Paolo Ardito reconnect on the Drawbridge (with Dario’s dog, Lupo) in 2010. (Photo: Jim Sullivan 2010)

We worked over 10 years building underground, often seeing daylight only at lunchtime. We completed more than 80 rooms underground, each different, using all the ideas I had discovered after researching for many years in Europe. The square footage of the underground rooms alone, built on four separate levels, was nearly 80,000, or two acres. These rooms were to be barrel aging cellars and our wine tasting rooms.

Construction of the cellars under the Tasting Room in 1998.

In 2004, we finally finished the underground portion and began building above.

The Great Hall, entrance to Courtyard and North Tower under construction in 2005.

We constructed a dry moat, high defensive fortified walls, five towers, courtyards and loggias, a Tuscan farmhouse and other outbuildings. We erected archways, a big kitchen, a Great Hall that took one and a half years to completely fresco. We built stables, an apartment for the nobles, wine fermenting rooms, a church and chapel, secret passageways, and even a prison and torture chamber. I was bent on being totally authentic incorporating every element of a real 12th – 13th century Tuscan castle. I attempted to depict how castles evolved over time, by erecting doorways and niches and then bricking them up. We built a partially destroyed tower.

Entrance to the Courtyard from the Crush Pad in 2004.

Construction of the Drawbridge steps. The entrance to the Castello can be seen in the upper left. Photo taken in 2003.

View from the South Tower. Great Hall on the left, Upper Terrace on the right. Walkway to Great Hall in center. Photo taken in 2005.

Battle-damaged tower under construction in 2005. Farmhouse (far right) and fermentation rooms taking shape.

Castello di Amorosa appears to be an authentic castle for one reason only: it is an authentic castle, though fancified. We either used construction methods and materials that would have been used 1,000 years ago, or we used very old hand-made materials that had survived up to modern times. A fireplace predating Christopher Columbus adorns the Great Hall, and Iron Maiden from the late Renaissance dominates the torture chamber. A wrought iron dragon from the times of Napoleon hovers over the massive main door. More than 8,000 tons of stone were chiseled, not sawed, by hand to be absolutely authentic. Nearly 200 containers of old, hand made materials were shipped from Europe to lend authenticity.

We spent years sourcing old materials. Where we couldn’t find authentic handmade materials, we created them by using the same methods and materials of long ago. Fritz Gruber supplied me with nearly one million handmade, antique bricks from torn-down Hapsburg palaces. Georgio Mariani of Assisi in Umbria, along with his father, brother and uncle, made all lamps, iron gates and decorative iron pieces by hand over an open forge. Every nail, every chain link, every hinge and lock was hand-done by the Marianis. Their friend, Lucio, made all the leaded glass windows by hand. The Nanni brothers hand-carved all the ceiling beams. Loris Vanni and his brother-in-law Marino hand carved most of the door and window surrounds and the well. Dario Ruffini hand-carved the stone crests depicting my family’s coat of arms. There were many others, mostly from Italy, too numerous to name, who lent a hand to create the only real medieval castle in the United States. Even an Italian architect specializing in the restoration of medieval buildings, Frederico Franci, lent advice.

There were problems, from containers full of materials not arriving on time to the County making us re-grout virtually all the walkways and rebuild all the stairs, as they didn’t quite comply with local codes.

I kept declaring larger dividends than I normally would have from V. Sattui to keep afloat. But finally, in late 2005, I ran out of money. Enter Wells Fargo Bank– from which I secured a large loan. By mid-2006, I was nearly in a panic about going bankrupt and losing my entire property. I simply couldn’t continue to expend large sums of money I had invested in the Castle, the winery equipment, the vineyards and the wine inventory. It had been nearly 14 years without one penny back. I started selling some of the Castle wine cheaply just to raise money. I borrowed from V. Sattui as well as the bank. I was desperate.

Just as with the Castle, I had endeavored to make no compromises with the wines. We planted vineyards in 1994 through 1996. Yet we waited to make the wines until we had older vines to produce the highest quality.

Today Castello di Amorosa produces some of the best wines in the world from its Diamond Mountain District vineyards surrounding the Castello. (Photo: Alison Hernandez 2017)

Ramparts, towers, the guard tower and a variety of Castle defensive positions overlook the Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sangiovese and Primitivo vineyards. (Photo: Jim Sullivan 2010)

Finally, we were able to open on April 7, 2007. I had no idea if the project would be well-received or not. Would I be laughed at or would people respond positively? The first few days after opening gave me hope. The response to both the Castle and our wines was overwhelmingly positive.

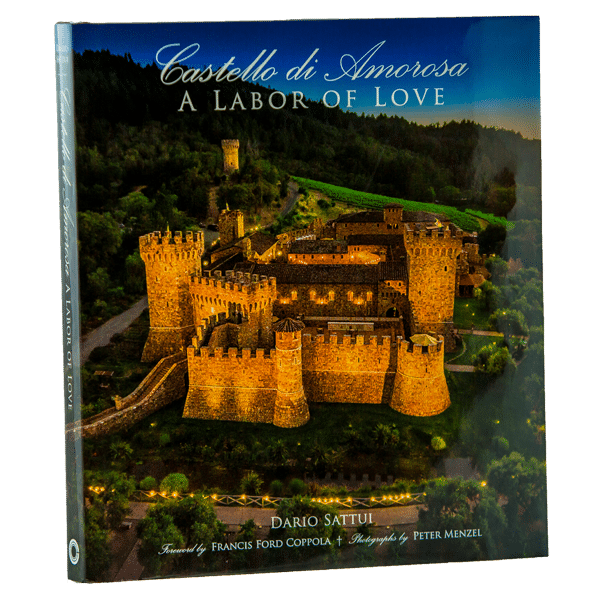

Read more about the story of Castello di Amorosa in Dario Sattui’s book, Castello di Amorosa: A Labor of Love